Kansas City's Own Chef Riedi and His La Bonne Auberge

Locations: 5209 Antioch Road, 610 Washington, & 725 Main Street, Kansas City, Missouri

Earlier this week, Chef Augustine “Gus Riedi passed away, to the sorrow of his many patrons, chefs, and restaurateurs here in Kansas City and across the country. A native of Rhäzüns, Grabünden, Switzerland, Riedi was born in 1932. Portions of the post below first appeared on my Facebook blog shortly after I published Kansas City: A Food Biography. In the work I did to prepare my forthcoming book, Iconic Restaurants of Kansas City, I enhanced the information, as seen in the updated post below. This post is in memory of Chef Riedi and the significant impact he made on Kansas City's understanding of what excellent food and hospitality mean.

"Chef Riedi was the hardest working--and fastest--chef I have ever worked with,” stated Susan Feniger, one of Riedi’s protegees. Her observation in an interview with me was seconded in almost the same words by another Riedi protégé, Kent Rathbun. La Bonne Auberge was one of Kansas City’s few serious French restaurants, and its rise to prominence was due to its indefatigable chef-owner, Augustin “Gus” Riedi, who arrived in the United States with impeccable culinary credentials but few connections.

Riedi’s success came down to an indomitable work ethic and quest for perfection--traits manifest not only in his cuisine, but in those of his protegees.

Riedi also stood out for his generosity and patience towards young chefs. He was part of Kansas City’s first organized attempt to train apprentices here rather than send them elsewhere, and as such he helped form the Greater Kansas City Chefs Association’s Apprenticeship (GKCCA) program. His former colleague, Klaus Sack, remembered him in his history of the GKCCA as “one of the best chefs in Kansas City, . . . a man of many talents.”

Riedi’s mentoring was so important that he was partially eclipsed by his students, but as with the best teachers, he was comfortable with that fact, secure that he was as instrumental in the future of cuisine as he was in helping turn Kansas City into a culinary destination.

Growing up in the Grabünden Canton, Riedi apprenticed at the Santorium Schatzalp and trained as well in Montreux, Interlaken, Geneva, and Zurich, Switzerland.

To improve his English and explore further options, Riedi moved to the United States to work as a butler in Beverly-Farms, Massachusetts, where his employer wished him to serve her eleven dachshunds “cereal on china dishes that cost $300,” Riedi explained to Kansas City Star reporter Jane P. Fowler in a December 17, 1972 profile. Having had enough of that, he took a friend’s advice and moved to Kansas City in 1958.

As with two other Kansas City Chefs of distinction, Jess Barbosa and Herman Sanchez, Riedi found himself initially at the Muehlebach kitchen scaling fish and butchering poultry.

Uncomplaining and hard-working, Riedi established his reputation and moved on to the Kansas City Club where he worked as sous-chef, and then Bretton’s, where he served as a chef. All the while, he saved his money in anticipation of owning his own establishment.

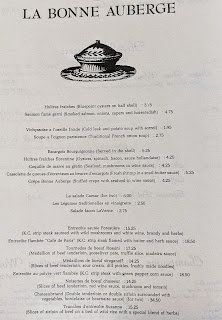

5209 Antioch Road in Kansas City's Northland was probably not Riedi’s first choice of location for his own restaurant, but the real estate was affordable, and Antioch Shopping Center’s expansion brought business. By 1971, Riedi was successful enough to transform his coffee shop into The Good Inn, or La Bonne Auberge. With the partnership of his wife, Laverne, the two focused on Continental cuisine, with Northern Italian and German specialties appearing alongside an assortment of French classics: entrees de poissons, de boeuf, de veau, and d’agneau. The cozy décor, that of a Swiss Chalet, made people feel welcome.

Chef Riedi was not flamboyant, nor was he an extrovert. He cooked expertly, knew what he wished to express on the plate, and went about his work with little fanfare. He was also reluctant to take on outside help because he struggled to “find anybody to trust,” as he explained to Fowler. An exception was Kansas City native, Paul R. Geelan, who worked his way up to become Riedi’s sous-chef. To expedite service, they reduced what Riedi had learned working in Zurich with a team of forty-seven chefs down a two-person operation where Riedi prepared the mother sauces (including hollandaise, veloute, and espagnole) and from there, based on what customers ordered, the secondary sauces essential to French classic cuisine. Mousseline napped cold poached salmon while bordelaise graced the chateaubriand.

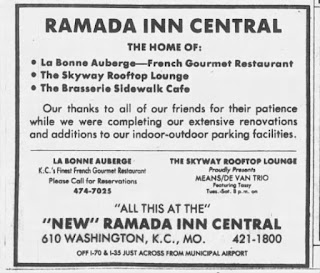

Customers were astonished to find such sophisticated cooking taking place in a suburban shopping center, and they started arriving from all over the Kansas City metro. Within a couple of years, Riedi took a gamble, moving downtown when in 1977, the Ramada Inn Central opened between Sixth and Seventh Streets and Washington. Riedi updated his menu and began systematically mentoring and training young chefs. An excellent carpenter, Riedi built his own trout and lobster tanks to ensure freshness. He specialized in fish and game. One of his most praised dishes, Caneton Bonne Auberge, was a duckling burnished with apricot, almond, and brandy sauce. His “delectable Escargots Bourguignonne” caused the Star’s entertainment editor, Shifra Stein, “to have a change of heart” when it came to snails. This regarded food critic echoed many others.

An early advertisement for the newly relocated La Bonne Auberge, September, 1977

Of the chefs who trained under Riedi, Susan Feniger and Kent Rathbun stand out. Chef Riedi “was a European chef with a great heart,” Feniger explained to Juliette Rossant in Rossant’s Super Chef: The Making of Great Modern Restaurant Empires. Finding out about Riedi from owners of the Swiss Confiserie, Andre’s, Feniger went to La Bonne Auberge and fashioned a deal with Riedi where she would work mornings for free and the dinner shift for pay; he agreed to the deal. “He worked from 7:00 am till midnight every single day. I would meet him there at 7:00 am and work till midnight,” Feniger told Rossant. Because Feniger was with Riedi literally the entire day instead of just on one shift, she took in all he had to teach “like a sponge,” learning about German wines, how to butcher, how to make pastry, how to create soufflés.

That foundation launched Feniger’s career, including Food Network hit, Too Hot Tamales, an appearance on Top Chef Masters, and her career as chef and restaurateur, co-owner with business partner, Mary Sue Milliken, of Border Grill Restaurants in Los Angeles and Las Vegas.

Feniger was still with Riedi when another apprentice, W. Kent Rathbun came on board. His mother, Priscilla “Pat” Rathbun, was La Bonne Auberge’s maître d' and floor captain, overseeing front-of-the-house operations with competence and talent, especially when it “came to table-side preparation of all the classic dishes, from steak Diane to crepes Suzette,” Rathbun recalled in an interview with me. It was virtually unheard of for a woman to have such positions as chef or maître d' at a fine-dining restaurant in that era, but like Feniger, Pat Rathbun was as committed and as hard-working as Riedi--and Riedi respected hard workers irrespective of age or sex.

It likewise made sense for him to take a chance on Pat’s seventeen-year-old son, Kent.

“Gus paved the road for me,” said Kent Rathbun. He took the young man through the Escoffier brigade, from vegetable prep and garde manger, up to the coveted sauté station. Riedi “was a great teacher. He took time to teach me, took time to show me technique,” Rathbun remembered. He learned in one year a two-year professional cooking curriculum, given Riedi’s commitment to Rathbun. And Rathbun excelled, absorbing Riedi’s work ethic and quest for perfection, virtues that stayed with him at the American Restaurant, in Thailand, and ultimately at his highly regarded Dallas restaurants, Abacus and Jasper’s. Rathbun and his brother, chef Kevin Rathbun also defeated Bobby Flay on the Food Network’s Iron Chef, and Kent carries numerous Beard nominations on his resume. He and his wife, Tracy, now co-own Dallas favorites Shinsei, Lover’s Seafood & Market, and Catering by Chef Kent Rathbun.

Work ethic, talent, and reputation could not withstand the steady decline of downtown commerce. Riedi gambled on the Ramada and promises of a revived River Market (then called River Quay) just across the highway, as well as revitalization of downtown from Sixth Street up through Thirteenth where Bartle Hall was supposed to “spawn sophisticated restaurants and sustain those that have endured hard times,” wrote Glenn Kramon in the Kansas City Star in August, 1976. Just three months before the new La Bonne Auberge was set to open, however, crime units bombed two River Quay bars, and what business had been revitalized was significantly compromised. Tourists did not arrive, and the Garment District where the Ramada was located struggled from the day it opened.

La Bonne Auberge eventually relocated in 1981 to 725 Main Street, the Sheraton Inn. An optimist, Riedi stuck by his conviction that if the food is good enough, people will visit, regardless of location; indeed, people continued to patronize the restaurant. When Sylvia and Colin Clarendon visited shortly after its move in 1982, they praised the décor in their guide book, noting its dramatic entrance through “an impressive wooden door” that “descends to the restaurant level,” they appreciated the wine list, and also the six-course prix-fixe dinner option. As in France, the salad followed the main course, and cheese preceded an outstanding dessert selection, especially vacherin de fruit, an “ice cream, strawberries and apple sandwich between two layers of meringue and covered with chocolate sauce.” The Clarendons concluded by praising how the new location allowed Riedi to enhance La Bonne Auberge’s reputation, “both in location and culinary art.”

My own first fine-dining experience in Kansas City happened at La Bonne Auberge around the time that the Clarendons visited. I was 17 years old and decided with my boyfriend at the time that we had to experience La Bonne Auberge for ourselves. Without a lot of money, he and I began saving spare dollars for the grand occasion, agreeing that it was best to go "Dutch." Never had I experienced such luxury, and admittedly, we were both a tad intimidated. Nonetheless, we were treated graciously, but when I was handed a menu that had no prices, I glanced anxiously at my boyfriend, whispered that I had no idea how much the items cost, and so he surreptitiously allowed me to glance at his menu to do a quick tally. I remember little about the meal other than Escargots Bourguignonne, my first experience with such a classic French dish, and I was immediately smitten.

By 1984, the restaurant that had introduced many Kansas Citians to French cuisine was no more. However, Riedi’s name lives on in Kansas City and the United States in part because of his students, and for him, that fact likely pleased him greatly.

Use MyRoofAI to make smarter real estate decisions in Pakistan. Get AI-powered price analysis, market trends, and more — all in one place.

ReplyDelete